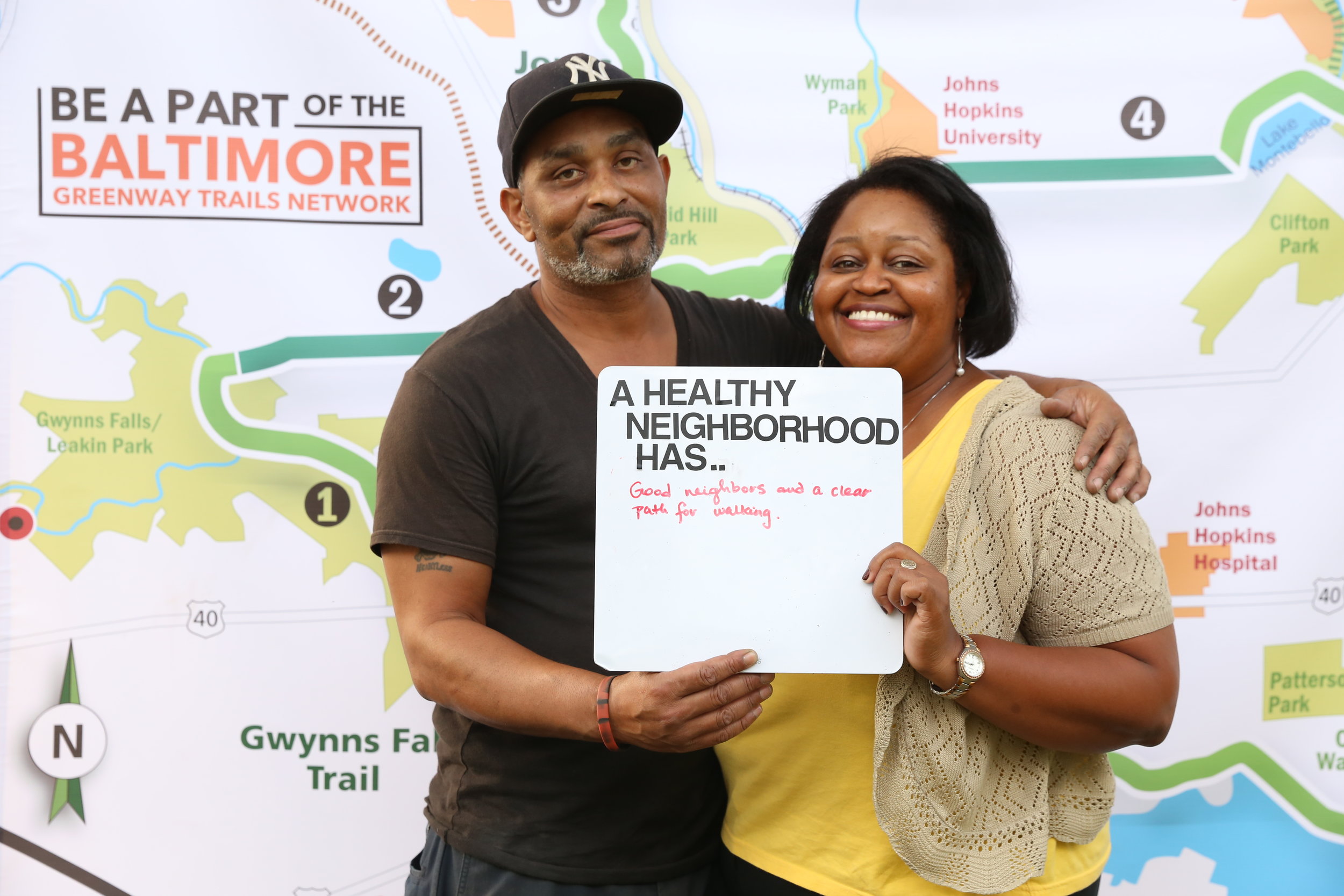

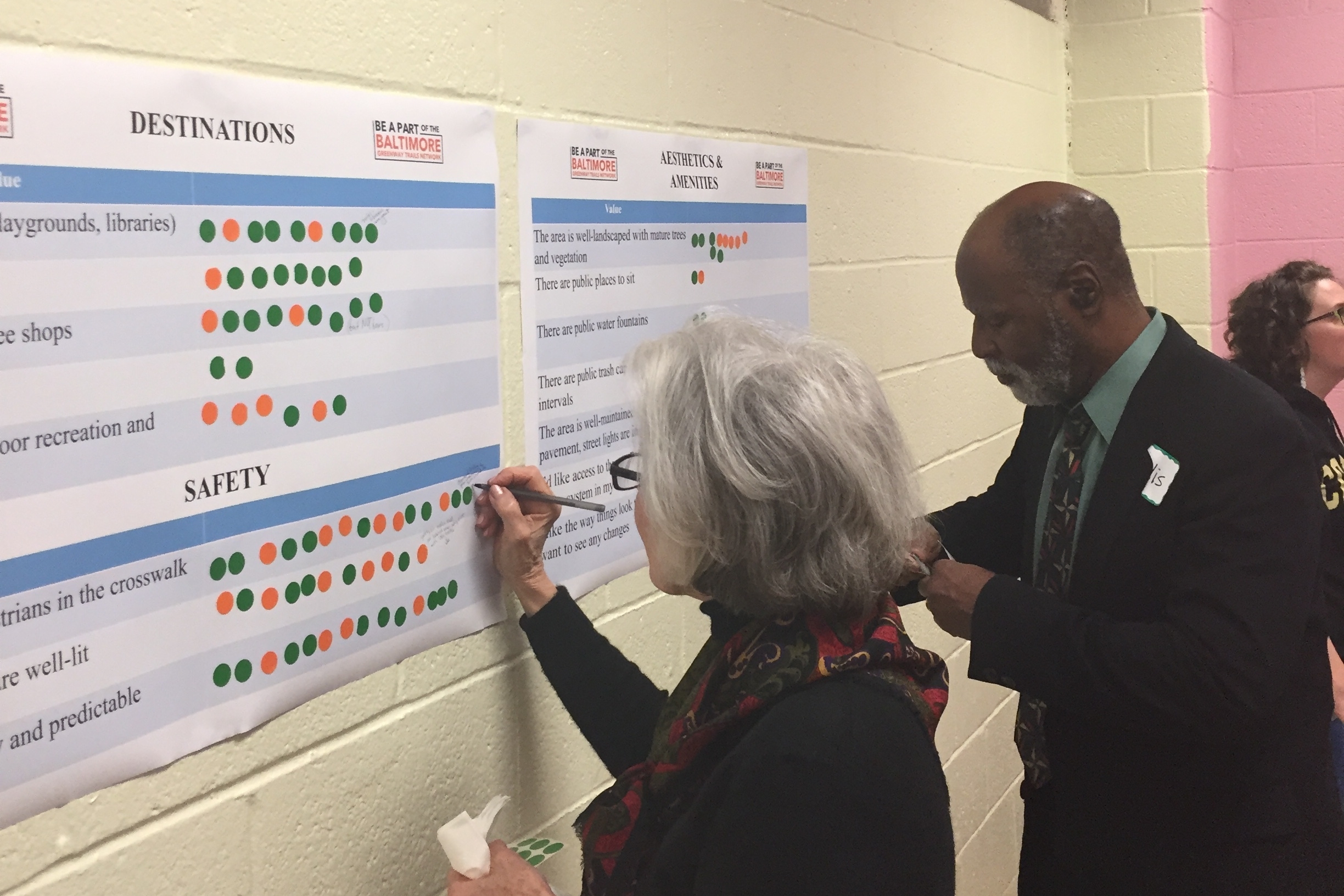

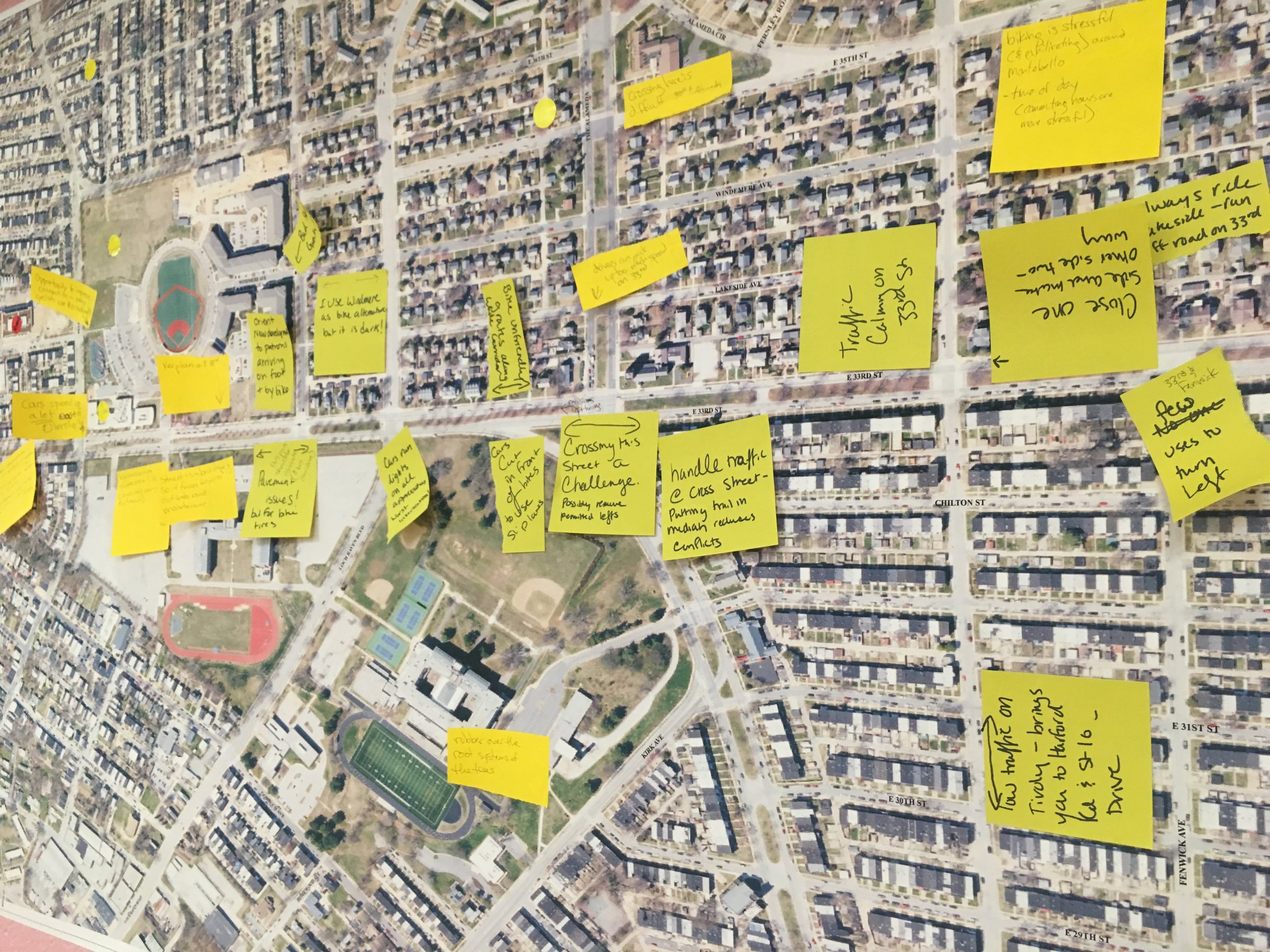

Bikemore is part of the Baltimore Greenway Trails Coalition, funded by a Plan4Health grant from the American Planning Association and the Centers for Disease Control. Over the past year, our partner and lead on the project, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, has hosted over a dozen meetings with residents and stakeholders adjacent to the Gwynns Falls Parkway and 33rd Street corridor. At these meetings they discussed using these two streets to connect the Gwynns Falls Trail, Jones Falls Trail, and Herring Run Trail into an eventual 35 mile trail loop in Baltimore City where people can walk or bike safely in a dedicated space separated from mixed traffic.

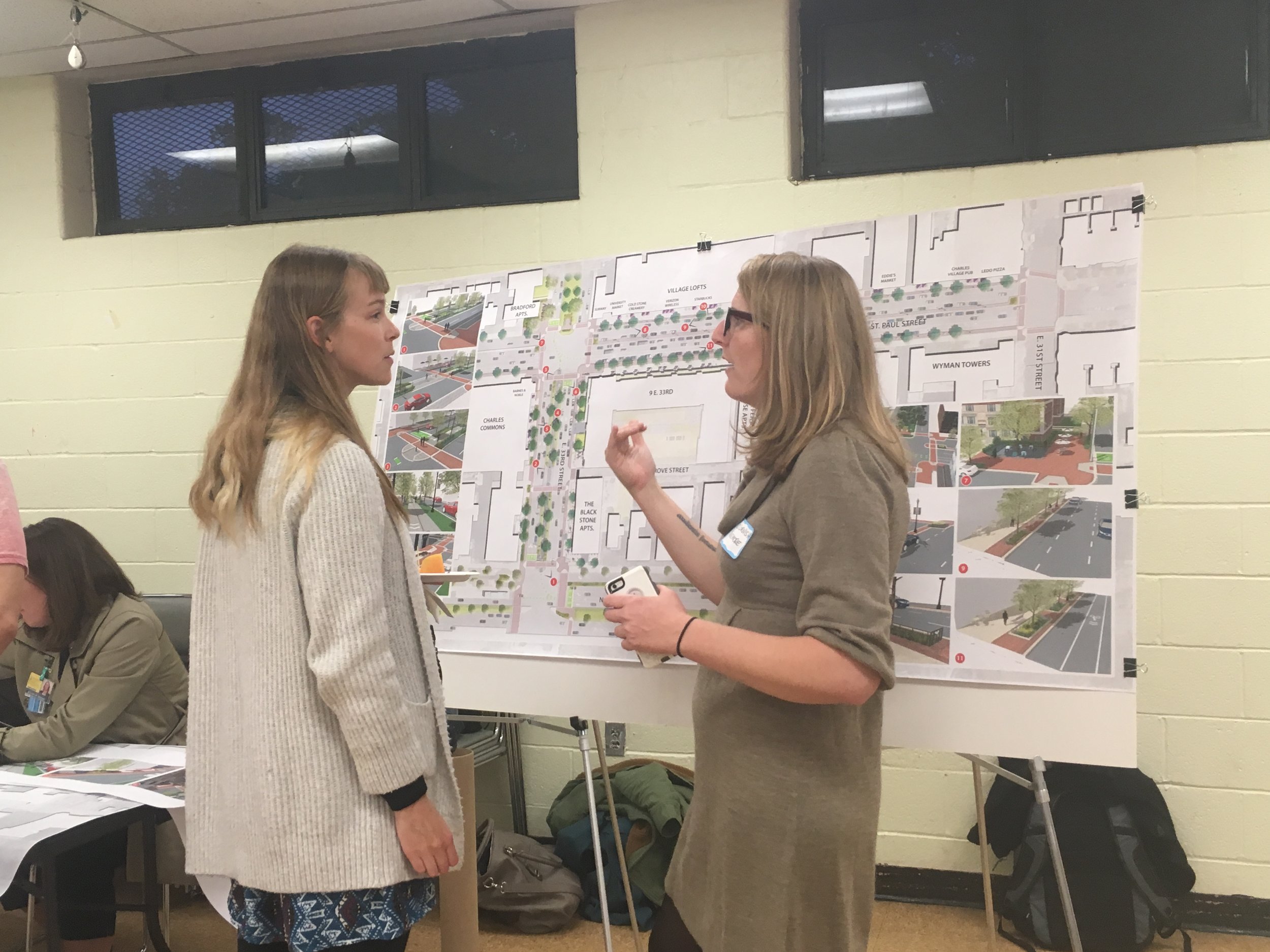

One of the options proposed for 33rd Street and Gwynns Falls Parkway is a two-way, on street protected bike lane.

The other is a center-running, multi-use community path. The advantage of this option is that it could be used both by people walking and biking, as well as neighbors who just want to recreate outside their homes.

This isn't a new idea. The coalition is building on and supporting existing initiatives, including Parks & People’s One Park Concept, Baltimore City’s Growing Green Initiative, the updated Baltimore City Bicycle Master Plan, the Open Space and Parks Task Force, and a revitalized master plan for the Middle Branch. Going back further, it works to bring the original Olmsted vision for Baltimore's "Parkways" to life.

A Brief History of Olmsted Parkways

The revised Olmsted vision in The Baltimore Sun, July 26, 1914

The Olmsted Brothers Company is responsible for the design of both 33rd Street and Gwynns Falls Parkway, among other parkways and boulevards in Baltimore City. The original intent and goal of these "Parkways" was to bring "Parking" (of the green—not car—variety) into communities, and connect Baltimore's entire park system via linear parks containing designated spaces for people to enjoy the park system by foot, car, bicycle, horse, or carriage.

Rapid city growth led to push back around the size of the right of way required to implement this plan. The result was the series of narrower boulevards present in our city today. Automobile based planning decisions in Baltimore, since these boulevards' construction, have turned them into high-speed automobile corridors, far from the original intent. Luckily, we can look back at the Olmsted vision for Baltimore, as well as to more successful implementations in other cities to see how we could better reprogram this space to match the true Olmsted intent.

The Olmsted designed Lincoln Parkway in Buffalo was planned with a multi-use, protected trail for people walking, biking, or riding.

Lincoln Parkway in Buffalo today looks much like 33rd Street, albeit with wider medians. While beautiful, it is rarely used by people.

The Olmsted Designed Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn in the 1930's with a multi-use median path for people walking and biking.

Today, Eastern Parkway retains the multi-use median path for people walking, biking, playing chess, or sitting on benches.

The Olmsted designed Brooklyn Ocean Parkway's multi-use path was split to include a "bicycle highway" in the 1890's.

Brooklyn's Ocean Parkway retains bicycle and walking paths today.

Project FAQ /Fact Check

While this is an exciting project that will serve all of Baltimore, and which has the potential to address a number of health, access, transportation equity, historic preservation, and quality of life issues for the whole city - some residents have expressed concerns about potential changes to the public space. A few others have spread false information about the project.

This is just one piece of a 35 mile trail vision. If this one stretch fails to materialize like the rest of the trail, the economic, public health, and transportation benefits of the entire trail system are in jeopardy.

We address some of the concerns here:

Some neighbors say this will remove green space

The proposed multi-use path, one option being explored on the corridor, will enhance green space. Currently, the medians serve as a green barrier to high speed automobile traffic. Activating this space with a multi-use path is one step in reclaiming the street for all road users.

The proposed median path would actually add active green space by lengthening medians and closing some of the "u-turn" locations between the existing medians to reduce high speed car traffic cutting through neighborhoods.

In addition to the median path, additional trees, shrubs, and rain gardens would be implemented to control and treat stormwater. Currently, the median has soil that is severely compacted and does not effectively treat storm water.

But some neighbors said you'll pave the median and kill all the trees

While a paved surface is the most ADA compliant and accessible surface, no decisions have been made about trail materials. There are many options. A "floating trail" can rest on the current median surface, and there are many other permeable paver solutions. The Indianapolis Cultural Trail is an example of a "floating trail" surface that is permeable and does not disturb existing plantings. A soft surface trail also allows water infiltration without tree root damage.

The next round of study for this project will include specific planning and specifications for tree care as well as trail surface. There are many examples across the country of trail and path construction coinciding with tree care and maintenance.

This would be dangerous for everyone

The current design of these roadways is dangerous for everyone. The floating unprotected bike lanes are substandard, the sidewalks have too many street crossings, and the wide travel lane allows cars to drive too fast.

The proposed redesign would be engineered to the highest safety standards to protect trail users, residents, and people driving along the corridor. All crossings would prioritize the safety of trail users. Traffic calming would be a significant part of the design of the entire corridor.

This plan isn't historic or destroys the Olmsted Vision

See the above background on the Olmsted vision for these parkways. This plan introduces many elements of the historic Olmsted vision, and will ultimately achieve the Olmsted goal of connecting Baltimore City's major parks via parkways that can be safely enjoyed by city residents by foot, car, horse, or bike.

So, what can I do if I support this plan?

#FillTheRoom for the next

33rd Street Open House

April 25th | 6:00 - 7:30pm

29th Street Community Center

RSVP and invite your friends and neighbors here!